Welcome to Political Disruption, the fortnightly newsletter on how politics disrupts business. In this first post we’ll explain the objectives of this newsletter and the rationale behind it.

Political Disruption - Your update on political risk

In this newsletter, we’ll analyse political events that could cause political disruptions of markets, supply chains or transport routes. We provide you with the context needed to understand how these events may threaten your business or create new opportunities.

Specifically, we consider how international conflict has and might have an impact on supply chains, how economic statecraft is evolving and could impact your firm’s market access and sourcing and how the digital domain is developing as the next frontier of geopolitical conflict through a cyber attack and information warfare. We’ll focus on the new face of political risk.

The old face of political risk

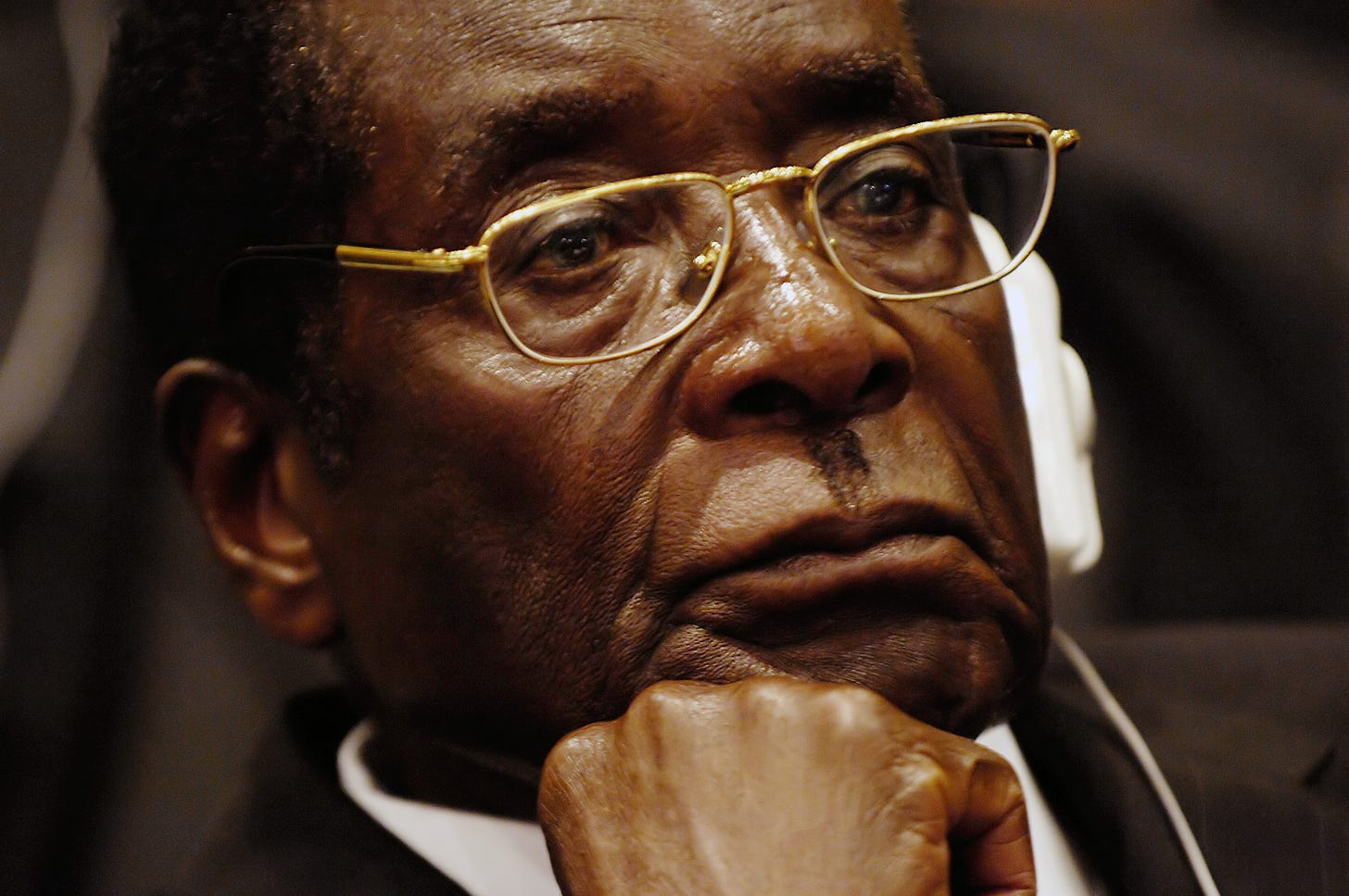

Until quite recently political risk was seen as something of concern to a few (mostly extractive) industries. Oil and mining firms faced the threat of expropriation and contract cancellations when they were doing business in faraway places like Africa, Central Asia or Latin America). The whims of authoritarian leaders like Hugo Chave or Robert Mugabe (pictured) caused political risk. Political instability, violence and social unrest sometimes threatened local assest. Political risk was country-specific.

Transformation

However, political risk has gone through an enormous transformation after the end of the Cold War. Two significant evolutions in the international environment lay behind this transformation:

The world got flat

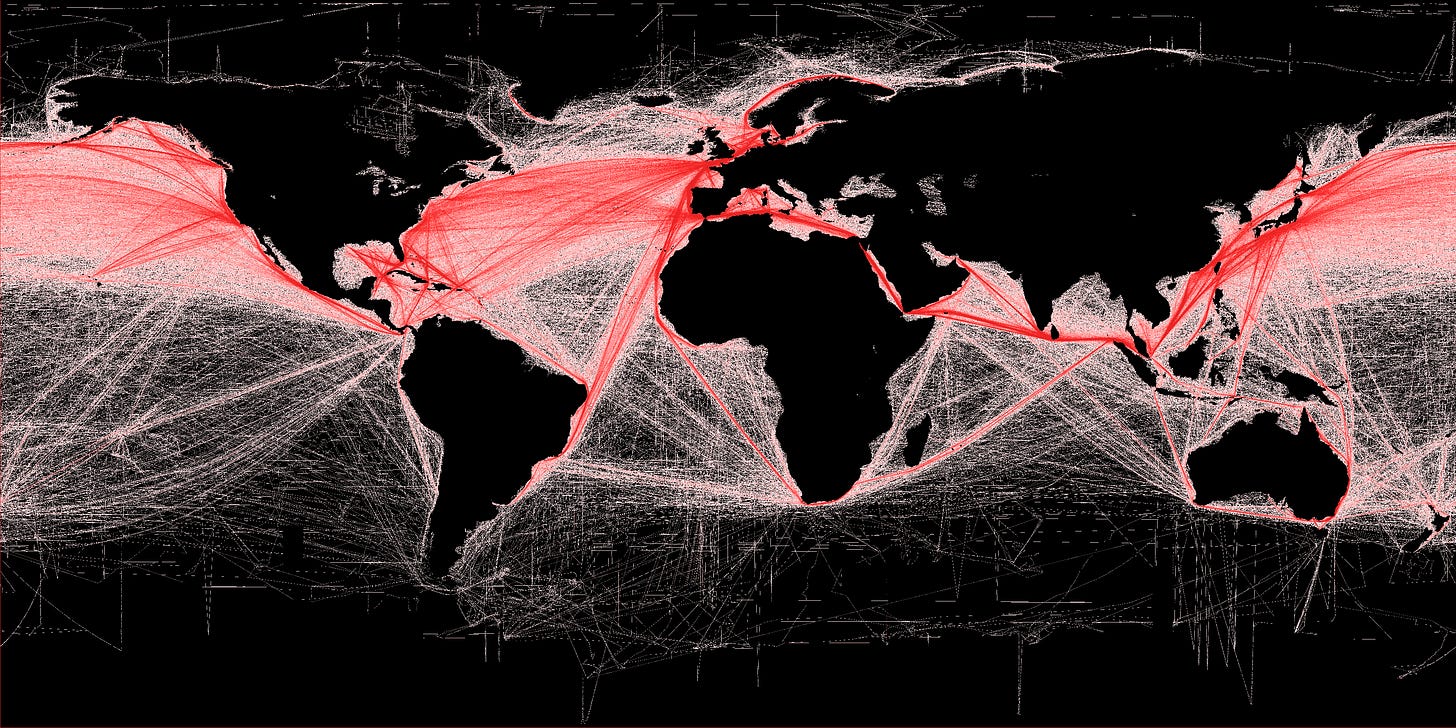

With the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union two previously strictly separated economies started integrating into one economic space. Also, countries in the developed world begun participating in the world economy. So a gigantic global economy emerged, creating enormous opportunities for those firms that were ready to search for the most efficient locations for every aspect of their operation. Supply chains spread all over the world, and international trade in goods increased exponentially.

It seemed as if international boundaries had ceased to matter for business. The optimism of the nineties led to the belief that once these new economies got richer, their nascent middle class would demand more political rights. Then political liberalisation would follow economic liberalisation. With all states democratising geopolitical conflict would evaporate.

But not so flat

That this was an illusion became apparent in the new millennium, with the invasion of Georgia and Ukraine (2008 and 2014) by Russia and China’s more assertive policies in the East- and the South-China Sea. The explosion of conflict in the Middle East after the Arab Spring failed to bring democracy to the Middle East (except a fragile version in Tunisia) made clear that there would be no new age without geopolitical conflict.

Since then we’ve seen an increase in global tensions. We saw the UK choosing to break-up with the European Union; the US elect a President whose mission seems to be to bring down the international rule-based system and the rise of strongmen in Turkey, the Philipines, China and Eastern Europe. Tensions increased between the two biggest economies, the US and China and between the EU and the US, the two biggest markets. Meanwhile, the international system, that has for years moderated conflict between states is under siege.

Competitive interdependence

However, in this time of renewed geopolitical conflict, the economy is still globally organised, multinational corporations operate globally and even small firms depend on very long supply chains (sometimes without knowing) and sell in faraway markets. This combination of global supply chains and markets and increased political conflict between states creates new types of political risk, risks to the global networks that compose the global economy. Networks of trade, people, money and information that we took for granted a decade ago, are now at the risk of disruption.

States leverage the globalised economy in conflicts by the use of sanctions, boycotts, tariffs and cyber attacks for political gain. Less risky than military conflict but more forceful than just diplomacy, economic statecraft became the go-to strategy for states in the age of competitive interdependence.

Networks of risk

While the old political risk of expropriation or violence was a local risk for a limited number of industries that extracted resources, the globalisation of production has commoditised political risks to all economic sectors.

Besides, the increased use of economic statecraft increased the potential for the political disruption of flows between countries. Political risk became a network risk.

Typical to these networks is that events in one country might have an impact on the political stability of a country far away and seemingly unrelated events can cause substantial political disruption.

And this is how geopolitical risk is evolving. Seemingly remote events can cause cascading effects that disrupt your business.

This is the type of risk we’ll be dealing with in this newsletter. Each month you’ll receive an overview of political events having an impact on market access, supply chains and transport routes.

Please feel free to forward this email to colleagues who might be interested in how political events create risks and opportunities for business. They can subscribe here.